🧵 The Thread and the Marsh

A Manual of Letting Go

“Memory is repetition with a difference… a wheel that turns, returns, and turns again.”

— Simon Critchley, Memory Theatre

🤜Prologue: A Chosen Unravelling

I knew this would be my final excursion in Japan. That knowledge pressed gently on the edges of everything: the packing, the planning, the long transfer out of Tokyo. I didn’t want a climax: no neon goodbye, no return to a sacred mountain. I wanted something slower. A place where the silence could settle. A space to feel what leaving meant.

So I chose Tomioka and Oze. One built by thread, the other saturated by water. One shaped by rhythm, the other by absorption. I didn’t know exactly what I was seeking; only that I wanted to move from something held to something let go.

This is not a guide. It is a manual in the older sense: something made by hand, shaped through slowness. A record of movement not just through space, but through meaning. What follows is a meditation on metaphor, memory, light, and longing: on how a thread can become a path, and a marsh, a way of walking without destination.

I. 🏭 Tomioka: The Loom and the Absence

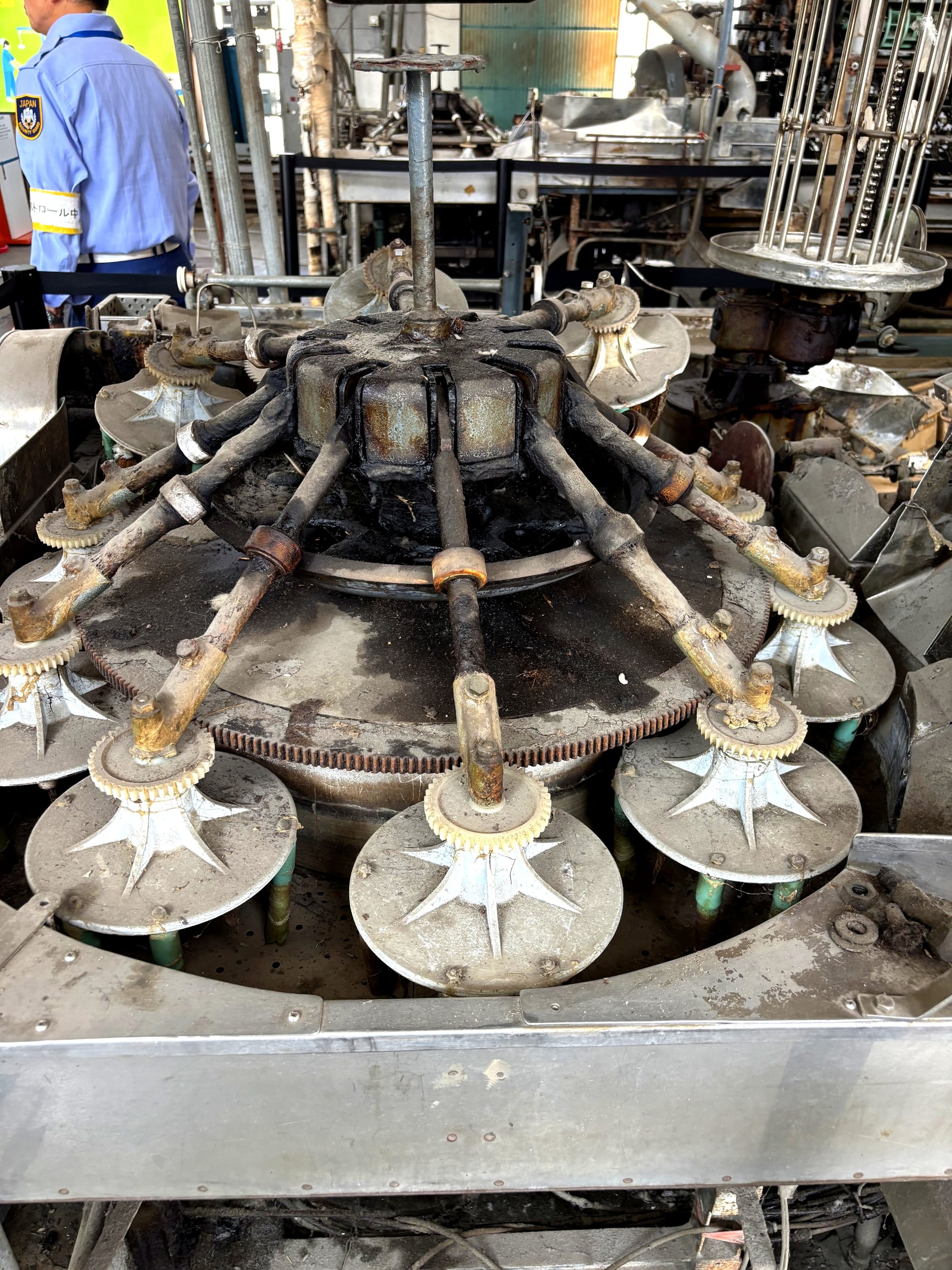

Tomioka is a town built on rhythm. Japan’s first modern silk-reeling mill opened here in 1872, constructed with French technology and Meiji ambition. Silk was not just an industry. It was diplomacy. Modernity. A dream woven outward from the body of the nation. The mill’s women workers, most of them young, were not simply employed; they were instruments of transformation.

Today, the buildings are silent but proud. Brick façades, orderly beams, vast windows letting in soft, controlled light. The stillness feels deliberate, as if curated to suggest reverence. But it’s too clean. The machines are stopped. The signs explain everything. And still, something is missing.

I thought about what Jon Fosse calls in Septology a shining darkness full as it is of nothingness. That was the texture of the air in Tomioka: bright but hollow. The past gleamed, but what had once filled it was gone. No fatigue, no chatter, no ghosts of the women who bled their fingers on cocoons. Only the idea of them.

George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, in Metaphors We Live By, write:

“Metaphor is imaginative rationality… creating coherences by imposing gestalts structured by natural dimensions of experience.”

Tomioka is metaphor imposed. A loom is a metaphor. Thread is a metaphor. History, in Tomioka, has been spun into coherence: into something the nation can wear. But coherence always leaves something out. Beneath the structure, I felt unease.

In English, we wish each other good luck: a gesture to chance. In Japanese, it’s ganbatte: do your best. Endure. Try hard. The wish is not for fortune to favour you, but for you to persevere through it. Tomioka breathes that ethic. Everything here, from the symmetry of the architecture to the silent choreography of machines, says ganbatte. Work well. Work long. Work silently.

But the marshland I was moving toward had no interest in effort. It would not reward determination. Oze is not something to be conquered. It is something to be entered, allowed. In Tomioka, I had admired what could be made. In Oze, I would learn what could not.

II. 🛤 The Road That Loosened

The journey into the interior took hours: a slow train from Takasaki, a smaller line to Numata, then a local bus climbing toward Hatomachitōge Pass. The landscape thickened as I moved. Factories gave way to rice fields, then forest, then cloud. Everything was damp: the air, my shirt, the wood of the bus windowframe.

Simon Critchley, in Memory Theatre, writes:

“Memory is repetition with a difference… a wheel that turns, returns, and turns again.”

That’s what this movement felt like. Not just the physical turn of the mountain road, but the echo of other journeys it summoned: the slow tram I once took along the coastline from Nagasaki to Shimabara, where the sea glittered like a thought I hadn’t finished. The winding bus ride from Gunma to Gujō Hachiman, through hills soaked in fog, where the silence between passengers felt like part of the scenery. Each of those moments returned now, reshaped by the knowledge that this was the end.

The industrial rhythm of Tomioka faded into something quieter: the sound of tyres on gravel, my breath in the valley’s thin air, the weight of memory pressed gently behind the ribs. The thread, I realised, had begun to loosen. Its purpose was fulfilled: it no longer needed to hold.

III. 🌿 Oze: Where the Marsh Refuses Metaphor

The first thing I noticed was the sound. Oze is not silent, it is full of cicadas, wind, boardwalk creaks, but the sound doesn’t echo. It settles. The marshland absorbs. I arrived on foot in the late afternoon, walking through pine forest until the trees opened like a breath, and the wetland appeared: flat, glinting, grassed. Still.

In August, Oze doesn’t offer much spectacle. The spring mizubashō have vanished. The yellow nikkōkisuge have browned. What’s left is presence: tall sedges, silver sky, the flick of dragonfly wings like small sudden thoughts.

The scent of it surprised me: damp bark, warm algae, something metallic where water pooled in the ruts. The boardwalk flexed softly beneath my soles, swollen from days of heat. Everything asked to be noticed, but not interpreted.

I walked slowly. Not because I wanted to, but because the marsh made me. It refused rush. It refused statement. And I remembered Fosse again:

“What matters isn’t what it literally says about this or that… it’s something else; something that silently speaks in and behind the lines and sentences.”

Oze does not want to be read. It wants to be entered. I tried to describe it, and failed. Tried to photograph it, and lost the light. The marsh does not lend itself to metaphor. It resists coherence. And in that resistance, it becomes strangely intimate.

There’s a Japanese word for the way the sunlight moved through the trees at the edges of the marsh: komorebi — 木漏れ日 — the light that filters through leaves. Not brightness, but broken brightness. Light that has been touched by something else.

In Tomioka, light was engineered: it fell in symmetrical shafts onto machines and spools. In Oze, light was given. It drifted. Shimmered on water. Warmed my back, then vanished in mist. Komorebi is not metaphor. It is the refusal of total vision: a kind of sight that allows for mystery.

IV. 🧘🏼♂️ A Stillness You Cannot Structure

I sat near the water, where the boardwalk forked and the marsh opened into distance. I had walked for hours. My legs ached; my clothes were damp; my body had settled into a quiet rhythm: not of striving, but of arriving. There was no view. No revelation. No photograph to justify the journey. Only the breath of air through the sedges, the faint rustle of water beneath wood, and my own pulse no longer seeking, only staying.

Perhaps that was the point. Not insight, but interruption. A break in the forward motion. A soft undoing of what had been knotted too tightly.

Fosse again:

”The human being is a continuous prayer. A person is a prayer through his or her longing.”

Perhaps that’s what I had been all along. A thread pulled across a country I never fully understood. A small prayer carried by trains, slowed by valleys, finally quieted by a marsh.

🤛Epilogue: The Gesture That Remains

In Tomioka, I saw the thread: tension, structure, purpose.

In Oze, I walked without it. The thread had done its work.

And in that walking, not toward meaning, but through it, I let myself arrive at departure. Some farewells are not spoken. They dissolve.

Not into absence, but into komorebi: light that lingers, filtered, in the space where something once passed through and left something behind.