🌲 The Path That Disappears: Tōno and the Brothers Grimm

“The tale is not beautiful if nothing is added to it.”

— Tōno Monogatari, Preface

📖 Two Books of the Forest

In 1812, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm published the first volume of their Kinder- und Hausmärchen. Their aim was not simply to entertain, but to preserve. Germany at the time was not a nation but a lattice of dialects and customs. The Grimms believed that the folk tale was a vessel of shared memory, a place where linguistic roots and moral intuitions intertwined. By recording these stories, they were not merely collecting curiosities. They were trying to recover a cultural ground.

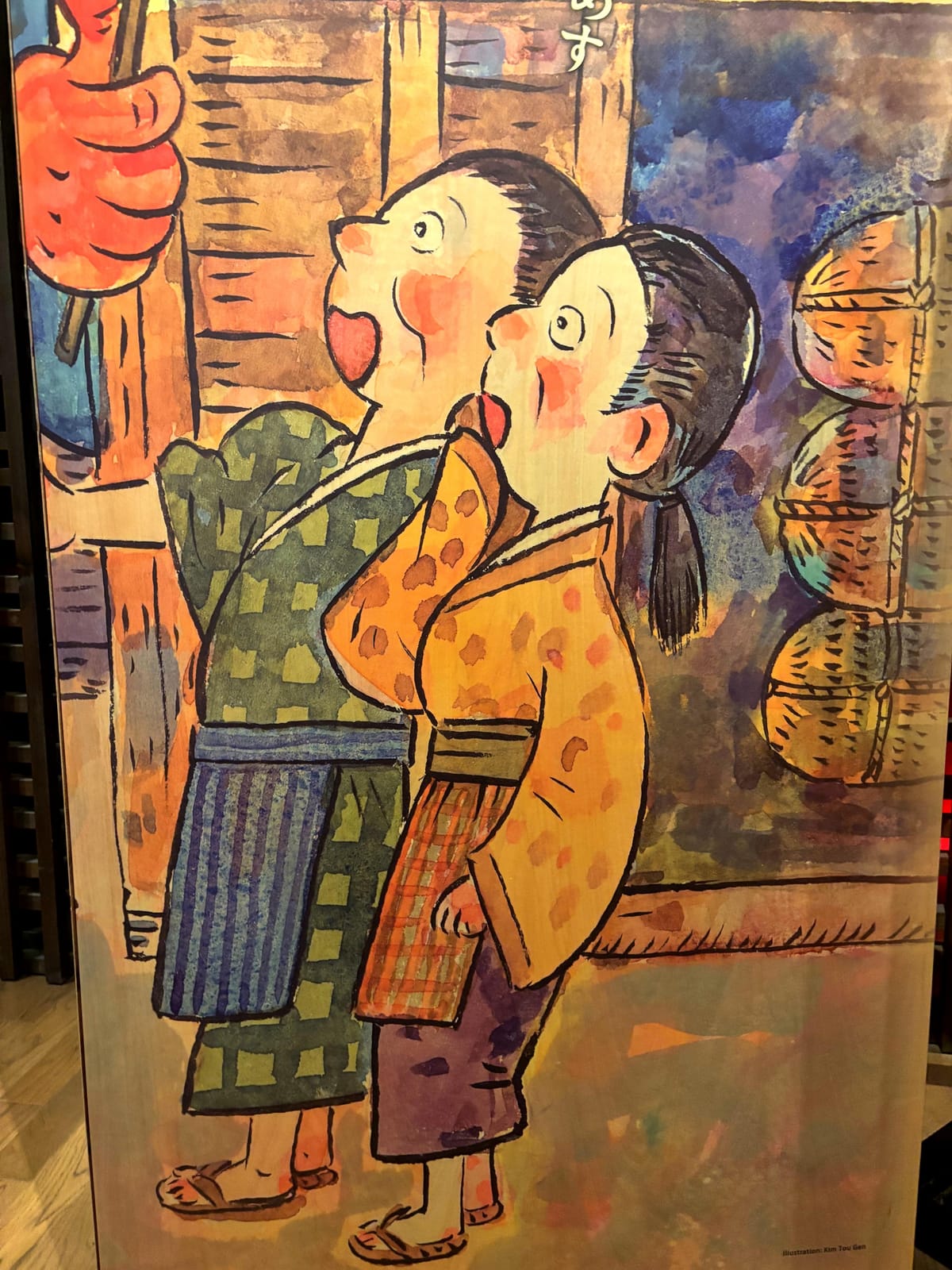

The tales they gathered are now among the most recognisable in the world. A girl walks into the woods. A wolf speaks. A house is made of gingerbread. A curse is broken by a kiss. The stories may be filled with enchantment and violence, but they move with certainty. Their structure is firm. Danger is met and overcome. The world may tremble, but it is put back in place.

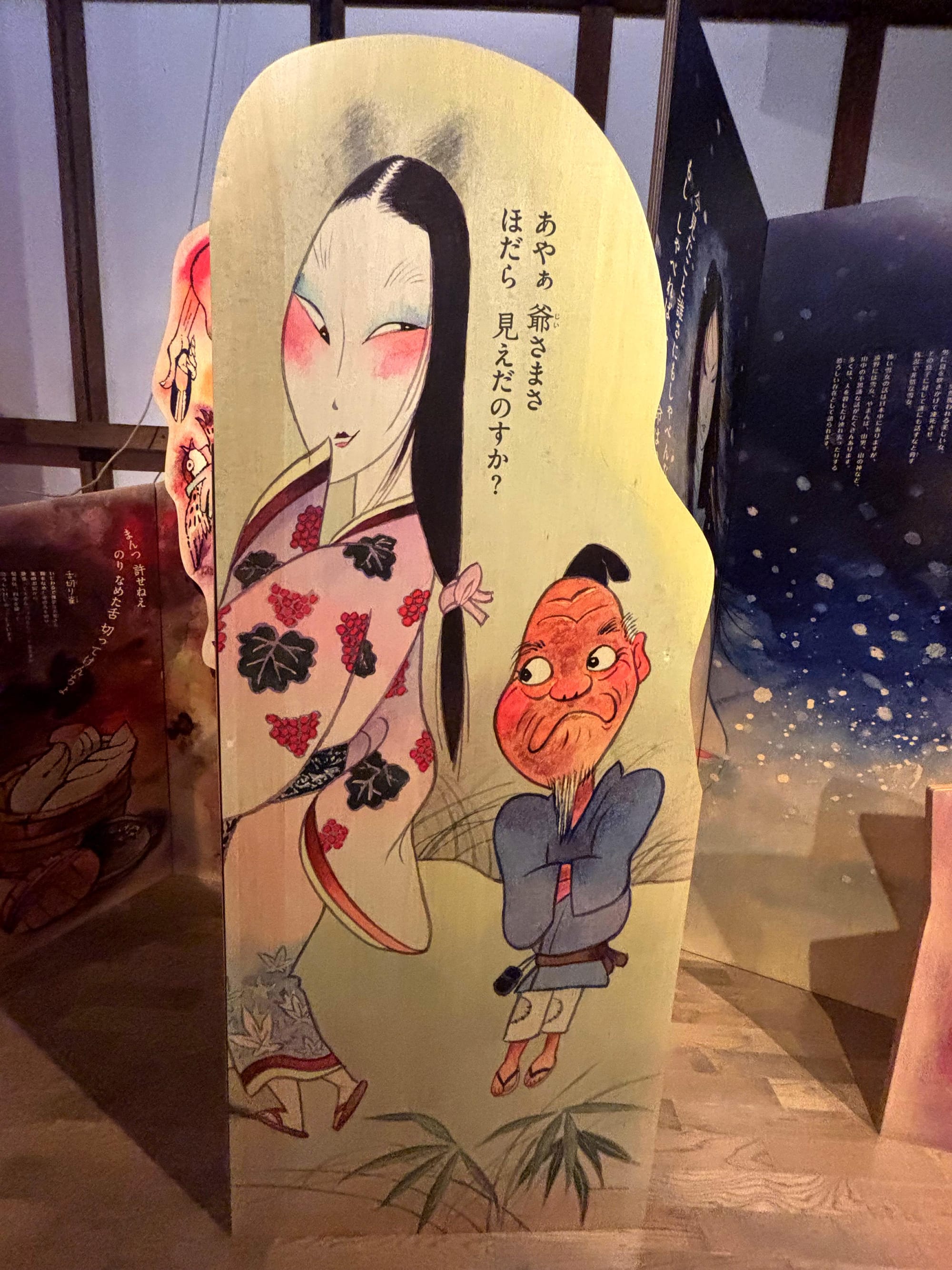

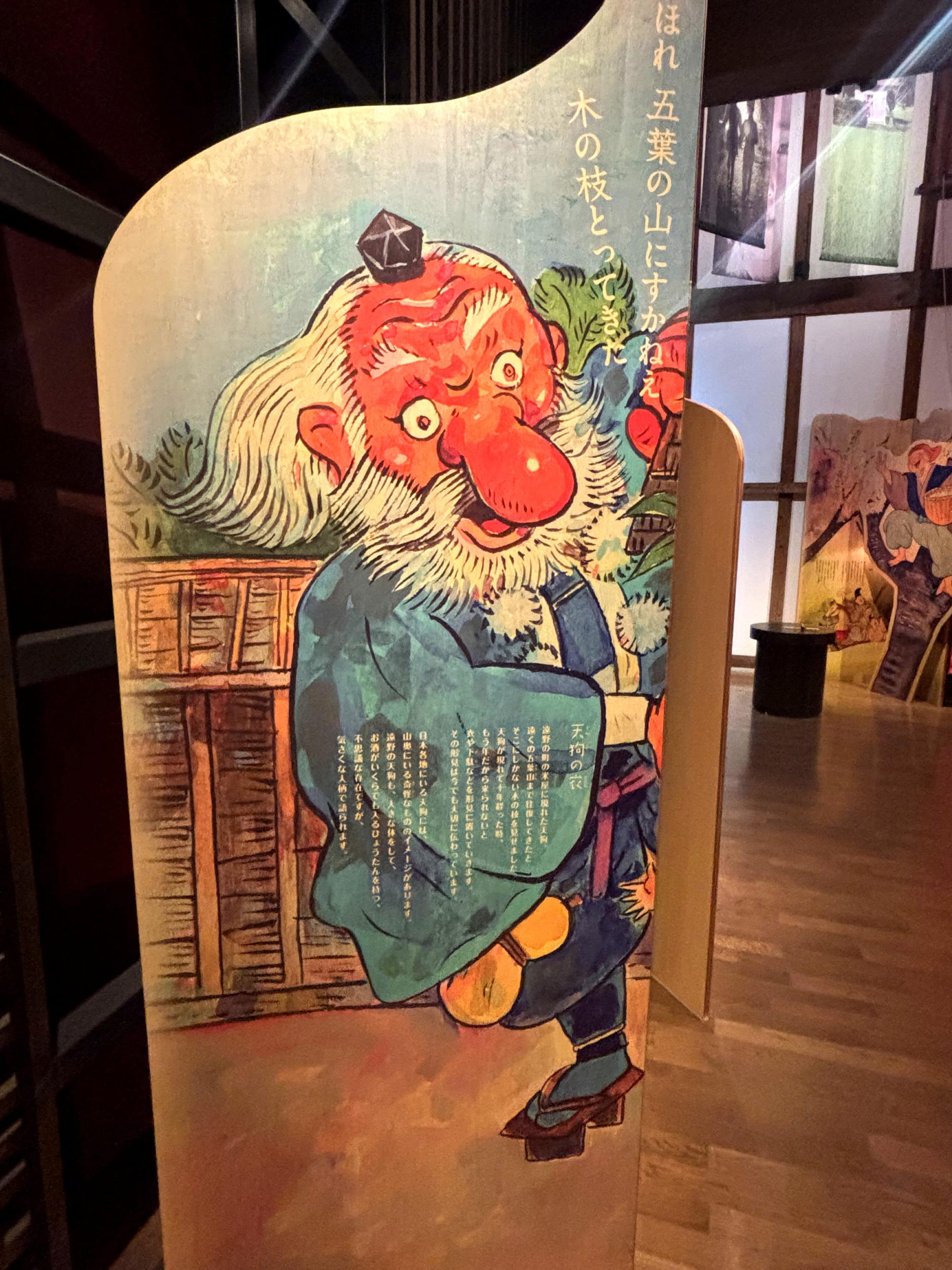

Nearly a century later, in 1910, Yanagita Kunio published Tōno Monogatari, a collection of stories recorded from the remote mountain town of Tōno in Iwate Prefecture. But these are not fairy tales in the Western sense. They have no princes, no triumphs, no final lines. They are sparse, ambiguous, half-told. A man hears a sound in the trees and is never seen again. A woman gives birth to a child with scales. A traveller remembers something strange but cannot say what it was. These stories do not teach. They do not conclude. They ask to be held, not solved.

The difference is not only cultural. It is philosophical.

Grimm tales are shaped. Tōno tales are suspended.

Grimm leads you through the forest. Tōno leaves you inside it.

📜 Aesop and the Logic of the Animal Tale

Long before the Grimms, Aesop was shaping a different kind of narrative form. His fables, composed over two millennia ago, are brief and didactic. They strip experience to its moral core. Animals serve as proxies for human traits. A crow learns not to trust flattery. A lion is undone by arrogance. A tortoise triumphs through persistence. Each tale is governed by clarity. The moral must emerge unambiguously. The story must end with instruction.

These tales are not encounters. They are arguments. They present a world without mystery. The forest is not a place of transformation. It is a theatre of consequence. Every act implies a law. Every animal is a cipher. The goal is not to wonder, but to understand.

In this way, Aesop established a Western habit: the idea that the value of a story lies in its legibility. A fable must deliver meaning. Its beauty is its utility. In Tōno Monogatari, this logic is foreign. The story is not judged by what it teaches. It is judged by what it evokes. And often, what it evokes cannot be named.

🧭 Propp and the Geometry of Plot

In the early twentieth century, Vladimir Propp studied over one hundred Russian folk tales and found in them a hidden grammar. He identified thirty-one narrative functions that could be used to map almost any fairy tale from the European tradition. A hero leaves home. A donor is met. A magical object is acquired. A task is completed. A return is made. The tale may wear different faces, but its movement is consistent.

Propp’s work did not only reveal how stories function. It revealed how the Western mind tends to organise meaning. Plot becomes a kind of destiny. Events unfold not as accidents but as necessities. Even the most chaotic tale obeys a structure. There is a promise that something is happening because something should happen.

This is what gives Grimm tales their peculiar gravity. They are enchanted, but they are also mechanised. The forest is a machine for shaping character. Danger is always symmetrical. The ending, however cruel, feels correct. Justice has a shape.

Tōno Monogatari offers none of this. It is not composed by formula. It does not unfold. It accumulates. The stories are not gears in a machine. They are fog rising in a valley. They may vanish before the listener realises what has begun.

🏡 Yanagita and the Geography of Memory

Yanagita was not compiling a system. He was listening to a place. The voices he recorded did not speak from abstraction. They spoke from memory. The man who heard a voice in the trees did not know what it meant. The woman who vanished after giving birth to something strange left no trace. The storyteller is not always sure. Often they admit uncertainty. They say, “That is how I remember it,” or “So I was told.”

The effect is not disordered. It is intimate. These are not fictions. They are testaments. The distance between the teller and the event is small. Sometimes just one generation. Sometimes the teller themselves is the one who saw.

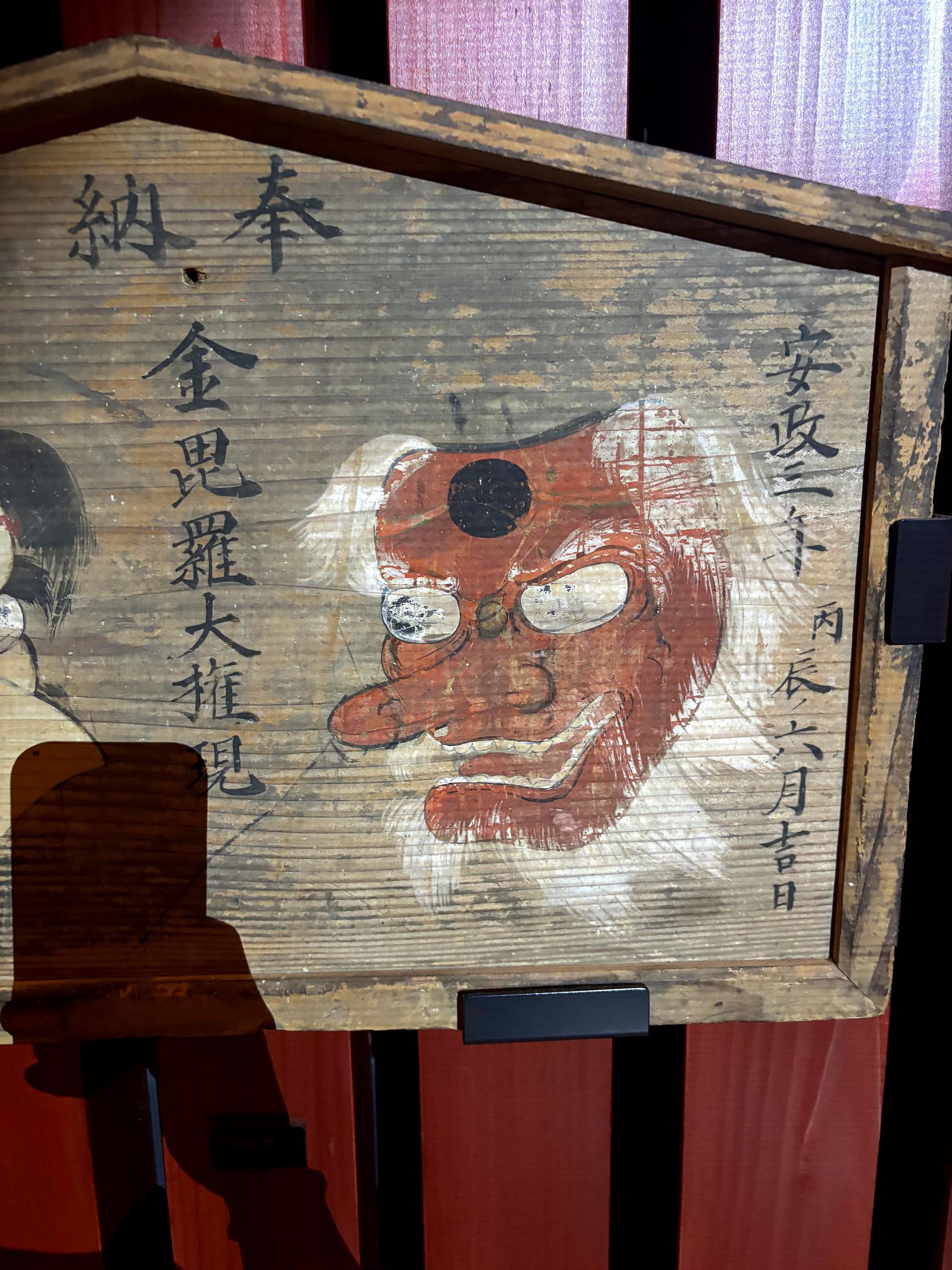

This makes Tōno Monogatari difficult to interpret and impossible to imitate. It is not designed to be retold. It is not transferable. These stories are rooted in a specific landscape, among specific people. Their truth is not general. It is local. And that is what gives them weight.

🏞️ Bachelard and the Poetics of Place

Gaston Bachelard wrote that we do not remember in time. We remember in space. A room. A stairwell. A slant of light. The places we inhabit are not passive. They shape the very texture of thought. To return in memory is to return in geography.

This is why Tōno Monogatari cannot be universalised. Its stories are saturated with place. The spirit appears not in “a village” but at a certain bend in the river. The strange noise is heard not at night, but near the second hill beyond the shrine. These are not backgrounds. They are coordinates of being.

In the Grimms, place is symbolic. The forest is a metaphor for danger, or sexuality, or transformation. In Tōno, the mountain is just the mountain. Its power lies not in what it represents, but in what it withholds. It does not interpret itself.

To dwell in these stories is to feel that the world is not empty of spirit. It is simply quiet.

🕰️ Time and Its Forms

Western tales unfold in sequence. Aesop’s is a morality of causes. Grimm’s is a morality of structure. Time moves forward. The story progresses. Meaning emerges at the end, like a fruit grown from earlier conditions.

In Tōno Monogatari, time behaves differently. It pools. It lingers. It repeats. A story may be only a sentence long, but it holds in the air like mist. There is no drive toward resolution. Often, the storyteller returns to a memory not to clarify it, but simply because it returned to them. Time in these tales is not linear. It is tidal.

The result is not a lesson or a conclusion. It is a presence that persists. A detail is remembered. A phrase is repeated. The story is not trying to arrive anywhere. It is simply not finished with us yet.

🧠 The Western Shape of Understanding

The Western folk tradition, from Aesop to Propp, is invested in clarity. Whether through structure or moral, the story is an instrument. It must give something. Its ambiguity, if present, must still be contained within a larger framework of meaning.

Aristotle famously wrote that a good story must have a beginning, middle, and end. Catharsis must be achieved. Resolution must occur. In many ways, this logic shapes the Western reader’s expectations. A tale must do something to the one who hears it.

Tōno Monogatari undoes this assumption. Its stories are not built for transformation. They are not engines of clarity. They do not arc. They do not cleanse. They do not judge. They testify. They remember.

And in doing so, they insist that the world is not always meaningful in a human sense. It is meaningful in a different register—one that can only be felt by presence, not by conclusion.

💭 A Thought for the Way Back

Aesop gives us fables. Grimm gives us myths. Both aim to shape the reader. The story performs a task. It explains. It completes. It gives form to fear and teaches how to survive the forest.

Tōno gives something else. It gives silence. It gives mystery. It gives the sense that a story has passed through you without fully landing. You are not the same, but you cannot say why.

So I left the museum in Tōno not with a sense of knowledge, but with a sense of weather. A change in the air. A tension in the ridgeline. A trace on the wind.

Not every story must explain.

Not every forest must be mapped.

Some are only meant to be entered.

And never left entirely.