🧱 Stone, Step, Gesture: On Nietzsche, China, and the Aesthetic of Ethics

“Morality is just a sign language of the affects.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

There are moments when travel ceases to be movement and becomes instruction. You do not merely see a country; you begin to feel how it has formed its people, its stone, even its silences. China did that to me.

I came to Beijing expecting monuments. What I found was something stranger and deeper: an ethics carved not in commandments, but in contours. An ethic not taught, but built. It was embedded in walls, rituals, and gestures that required no justification.

Nietzsche argued that morality has no divine origin. It is not given from above. It is made by human beings, shaped through repetition, resistance, and the expression of power through form rather than argument.

In China, I saw that truth everywhere.

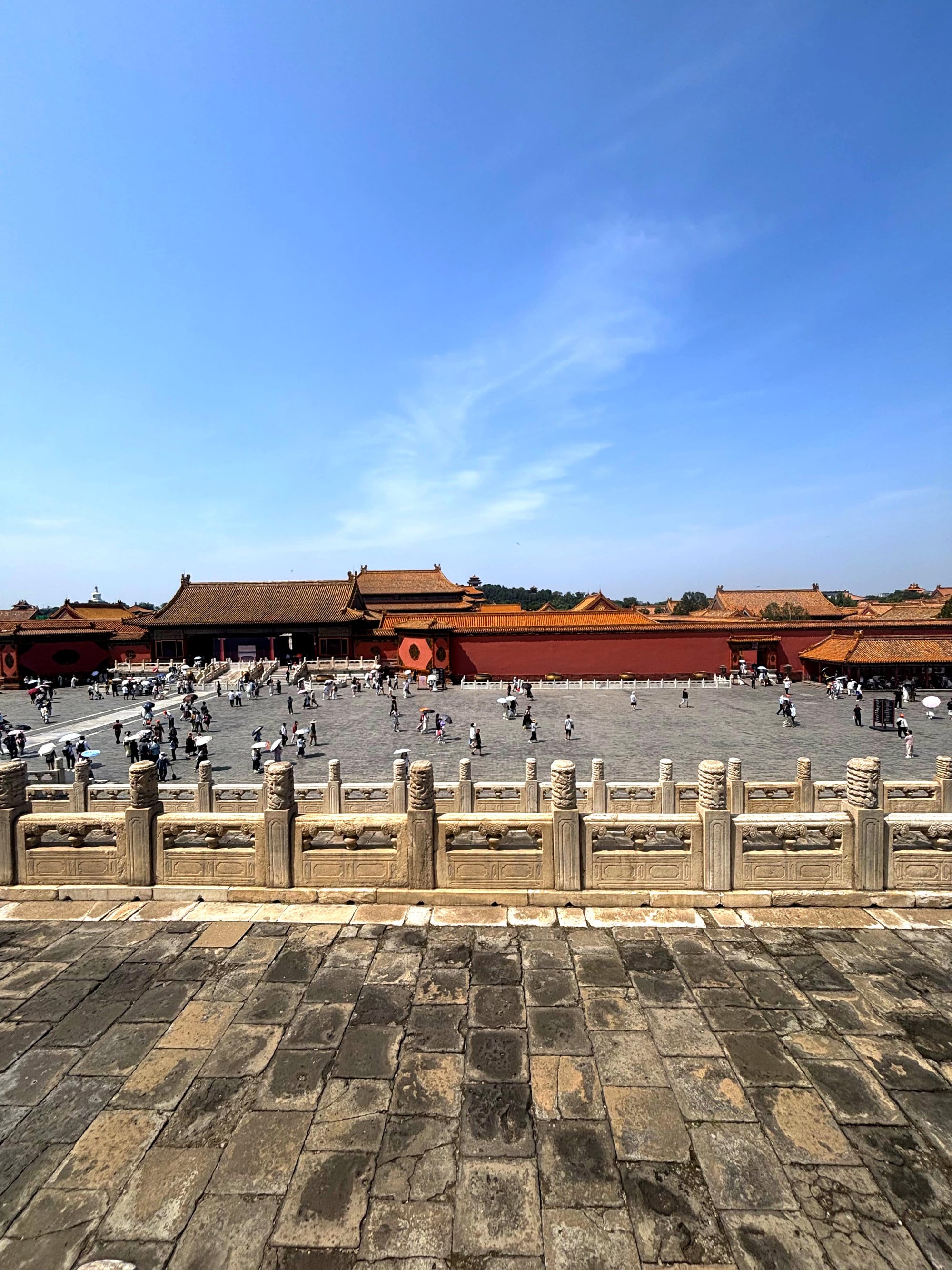

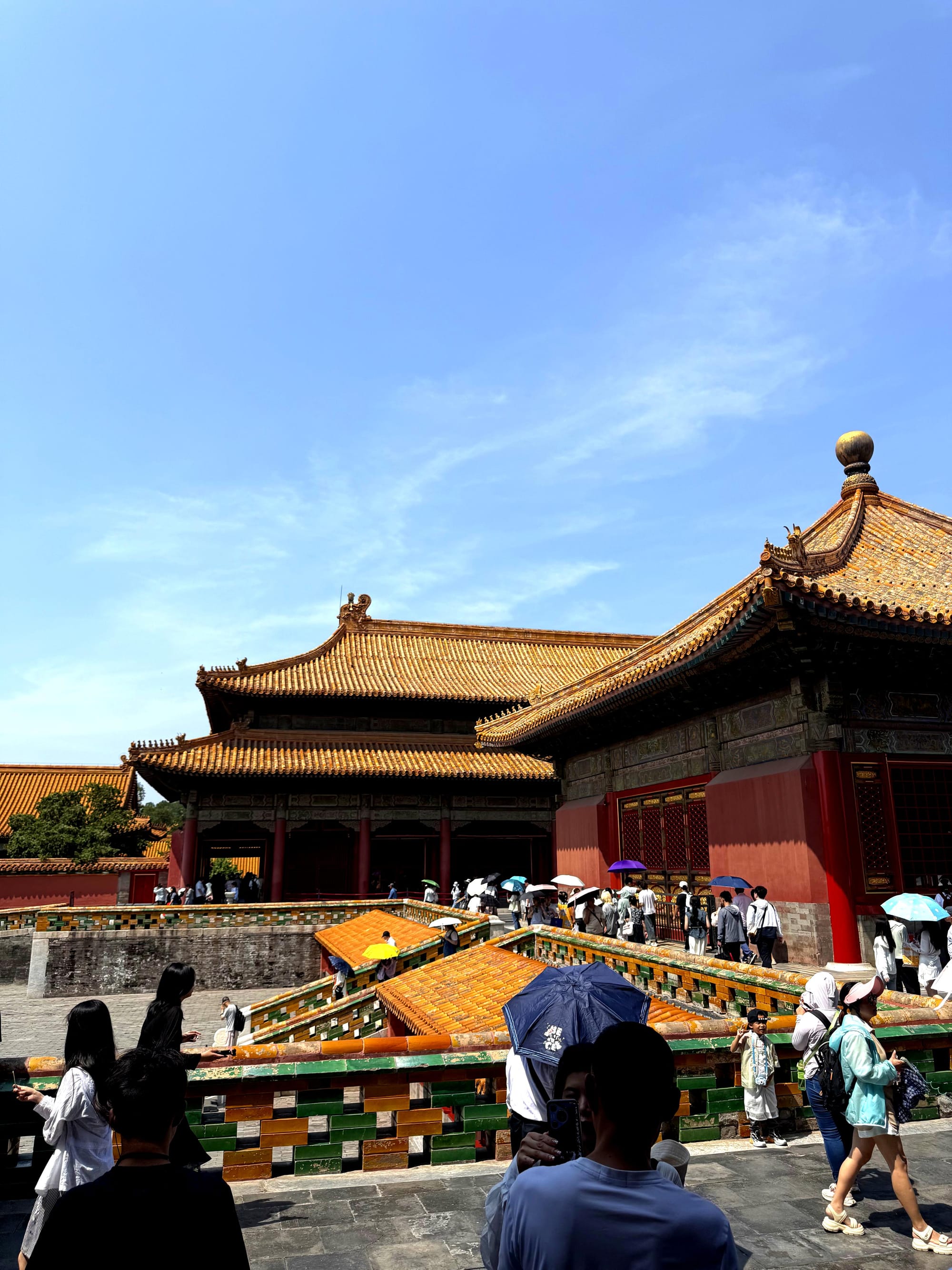

🏯 I. The Forbidden City: Order as Virtue

The Forbidden City does not instruct with words. It arranges. It does not demand belief; it evokes comportment. You walk straighter in its presence. Its halls are not merely architectural; they are judgments in wood and stone. The vast courtyards speak not of mercy or justice, but of order as a moral principle.

Nietzsche wrote that morality arises from the need to shape chaos into something endurable. This shaping is not always good in the abstract sense, but it is necessary for civilization to persist. The Forbidden City is the perfection of that impulse. It does not moralize through ideas. It civilizes through form. It channels power not by denying it, but by ritualizing its expression.

To stand in its geometry is to understand what Nietzsche meant by the aesthetic of morality. This is not moral beauty, but beauty as moral force.

🧱 II. The Wall and the World: Civilization’s Edge

The Great Wall climbs through the ridgelines north of Beijing like a spine. Its scale is staggering. It was built not only to repel outsiders, but to define what lay within. It is a boundary not simply between states, but between civilization and chaos. Nietzsche reminds us that civilization always constructs itself in opposition to something it calls barbaric. The Mongol horsemen who inspired the Wall’s construction were more than political enemies. They were the necessary opposites that allowed China to affirm its moral world.

What startled me was learning that this same wall had been sanctified by another empire. In the ninth century, Abbasid Caliph al-Wathiq believed that the Great Wall was the very structure built by Dhu al-Qarnayn, the Qur’anic figure tasked with imprisoning Yajuj and Majuj, two apocalyptic beings destined to return at the end of time. For al-Wathiq, the Wall was not a human artifact alone. It was God’s intervention to hold back cosmic disorder.

This symmetry is revealing. Both the Chinese and the Abbasids saw the Wall not only as a barrier, but as a metaphysical boundary. Nietzsche called this the mythic origin of value. Every ethic begins by defining what it must exclude. What we call good is often what we have enclosed. What we call evil is what we needed to keep out in order to preserve the coherence of the self.

🤝 III. The Man, the App, the Gesture

And yet, amid all this grandeur, the moment that has stayed with me was something small.

I had ordered a taxi from the base of the Great Wall. But the app (DiDi) locked in a pickup point over two kilometers away. I could not contact the driver, could not edit the route, and was stuck.

I turned to a Chinese man nearby and asked for help.

He responded without hesitation. When it became clear that I needed to take a shuttle to reach the taxi pickup point, he saw that my Alipay could not complete the booking because I lacked a Chinese mobile number. Without a word of complaint, he used his own personal number to register the service on my behalf. He contacted the taxi driver directly, arranged the pickup, and even sent the driver photos of me to ensure there would be no confusion. At no point did he ask for money. He never implied that the help required repayment. He simply acted, with calm precision and no expectation of reward.

Nietzsche wrote that the highest form of morality is not based on obedience or rule. It is nobility. Nobility means the readiness to give without calculation. It is generosity that requires no announcement. It is strength exercised without need for recognition. That man embodied exactly this. He was not virtuous because he followed a rule. He was virtuous because his habits, his disposition, his instincts had been shaped toward grace.

This is Nietzsche’s aesthetic morality. It is not something explained. It is something performed.

🌀 IV. Final Thoughts: Ethics as Inheritance, Not Argument

Nietzsche insisted that morality has a history because it has a function. That function is not abstract truth. It is survival through shape and stability. We build walls to preserve a world we can live in. We build palaces to ritualize the forces that hold it together. We cultivate gestures not because they are rational, but because they are beautiful in the old sense. They express alignment with something deeper than thought.

China made me realise that moral beauty is not softness. It is not sentiment. It is the inheritance of formed life. Life that has been shaped by space, time, repetition, and scale into something composed, restrained, and strong.

The Forbidden City revealed the grandeur of moral structure.

The Great Wall revealed the cosmic weight of civilizational defense.

And one man, helping quietly and precisely, revealed the ethic behind it all: to act, when needed, without needing to explain why.