Shizuoka: Between Mountain and Sea

🌊 Matter and Mind in the Morning

The sea greets me first in Shizuoka. From Shimizu harbour, gulls circle low as fishing boats return, the air woven of salt, diesel, and faint tea drifting from inland hills.

Armstrong cuts against the romance: the mind is the brain, nothing more. Awe and longing are patterns of neural firing, as material as the spray on the bow or the glint of scales in a net. But in refusing to place consciousness elsewhere, Armstrong makes the world more intimate. Wonder is not a ghostly presence, but matter in its most intricate form. There is no escape from this ground. To feel is to belong. To belong is to be bound.

🗻 The Surreal Line of the Mountain

From almost anywhere, Fuji interrupts the horizon. At times hidden in mist, at times sharpened into a geometry too pure to ignore, it demands attention. Breton rises with the mountain: beyond any preferences I recognize I have… what unique message I’m bearing, for whose fate I am solely responsible?

Fuji is not symbol but encounter. My neurons may explain the perception, but they do not dissolve the unease. The mountain does not answer me; it confronts me. Armstrong’s reduction grounds the scene, but Breton forces me to admit the surplus: the strange weight of my own singularity, pressed into awareness by stone and sky.

🏭 Industry and Labour

Shizuoka is not only mountains and tea fields but also ports, factories, rails, and smoke. Containers line the harbour, goods move through warehouses, workers load and unload with practiced rhythm. Industry here does not clash with the landscape; it completes it.

Armstrong is clearest in such scenes. The mind is matter, and labour is the extension of matter into form. Consciousness is not an idle witness but implicated in the world’s machinery: thought in the head, sweat on the back, gears in motion, all part of the same order. There is no clean separation between perception and production, between the neurons firing in me and the engines turning on the docks.

Responsibility here takes on a sharper edge: to acknowledge that the mind is material is to accept complicity in how matter is organised: in economy, in work, in survival.

🪷 Shuzenji: Impermanence and the Fragile Self

At Shuzenji, the temple precincts fold inward. Wooden beams are blackened with incense, chanting rises and falls like breath, and the river glides past, indifferent. Buddhism here whispers of impermanence that the self and its desires dissolve like smoke. To sit in the hush is to feel that nothing endures.

Yet outside the gates life insists: shiitake mushrooms grilled until soft, wasabi ice cream sharp enough to sting. These fleeting tastes vanish as they arrive. Shuzenji counsels release let the self dissolve into transience.

But Armstrong interrupts: there is no dissolving into nothingness, no hidden soul to scatter. The mind is matter, and matter endures by changing. Even impermanence is a material process, not an escape. The fleeting must be borne because it is real. For the Buddhist, release is salvation. For Armstrong, there is no salvation: only responsibility, carried through matter itself.

🔥 The Ground Beneath: Volcanic Shizuoka

Shizuoka is restless ground. Shuzenji’s hot springs bubble from volcanic depths, reminders that the earth itself is unstable, always shifting. To step into an onsen here is to feel the heat of matter in upheaval, the subterranean churn pressing against the surface.

Armstrong would call it energy, tectonics, the ceaseless reconfiguration of matter. For me, it is also a reminder that nothing is secure: even the ground conspires in impermanence. Breton would see in the eruption of heat a surreal charge, matter exceeding its form, desire erupting from the depths. Shizuoka is not tranquil: it is seismic, demanding awareness of the instability on which I stand.

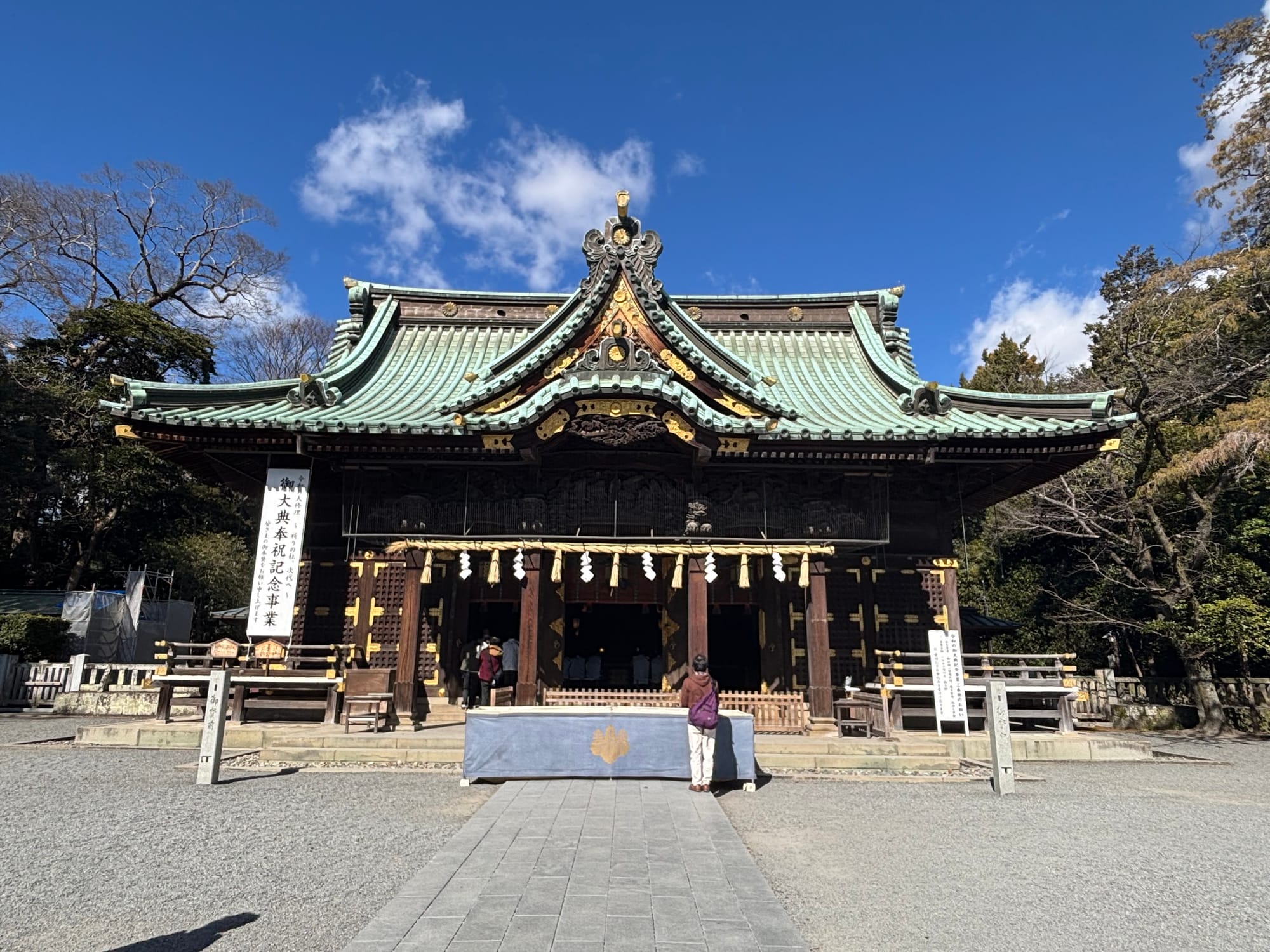

⛩ Mishima Taisha: The Breath of the Kami

Mishima offers another pull. Beneath vast trees bound with shimenawa ropes, the shrine is thick with presence. Shinto disperses the self outward, into fox guardians, flowing water, rustling leaves. Everything is alive, the world itself shimmering with kami.

Here the temptation is to lose oneself in animism, to let the boundary between self and world dissolve into spirit. But Armstrong refuses this too. No spirits animate the trees. What trembles in me is the brain’s resonance with light and sound. And yet to strip away kami does not flatten the moment: it sharpens it. If tree and self are both only matter, then reverence is kinship. The weight of obligation deepens: not to honour gods, but to answer the world itself, which stands before me as equal substance.

Between Shuzenji’s impermanence and Mishima’s animism, Armstrong’s materialism leaves me nowhere to hide. No release into void, no dispersal into spirit. Only matter, indivisible, inescapable.

✨ Responsibility of the Self Before the World

Shizuoka gathers its lessons and presses them into me. Armstrong denies transcendence: there is no outside. Shuzenji counsels release, Mishima dispersal, but Armstrong refuses both, leaving me with the stark fact of matter. Breton steps back in: what unique message I’m bearing, for whose fate I am solely responsible?

This is where the weight sharpens. If there is no spirit to dissolve into, no kami to absorb me, then I alone must bear the consequences of my perception. Fuji does not look back at me; it is I who must answer for the encounter. To taste mushrooms or wasabi ice cream, to walk among factories and ports, to feel volcanic heat rise through stone, to stand before temple hush or shrine forest: these are not innocent acts. They are mine, singular, unrepeatable. No one else can carry them, and no one else can answer in my place.

Responsibility, then, is not consoling. It isolates. It strips away refuge. Armstrong insists that I am nothing beyond matter; Breton insists that within this matter lies an irreducible difference. Together they leave me exposed, without appeal. I cannot vanish into impermanence or disperse into spirit. I stand before the world as myself alone, answerable without escape.

And yet this is also the possibility of freedom. If all weight falls on this world, then it is here, in the fleeting and the fragile, that meaning must be made. The neurons fire, the engines turn, the ground shakes, the world presses its claim: and I must reply.

To walk in Shizuoka is to feel the earth tilt beneath me. Not serenity, but vertigo. Not release, but demand. The task is not to resolve the tension, but to endure it, and to answer.